A $1 trillion economy by 2034 is a powerful headline but it is not a slogan you “announce” into existence. It is an outcome you engineer through macro stability, productivity gains, and a relentlessly scalable export-and-investment engine.

The arithmetic is sobering. Bangladesh’s GDP was about $450.1 billion in 2024 (~$470 billion in 2025), which means the economy must more than double in less than a decade in nominal dollar terms (World Bank Open Data) That “nominal” qualifier matters: even if real growth improves, persistent exchange-rate pressure can erase hard-won gains in dollar GDP. In other words, the path to $1T is as much about foreign exchange earning capacity (exports, remittances, investment inflows) as it is about domestic output.

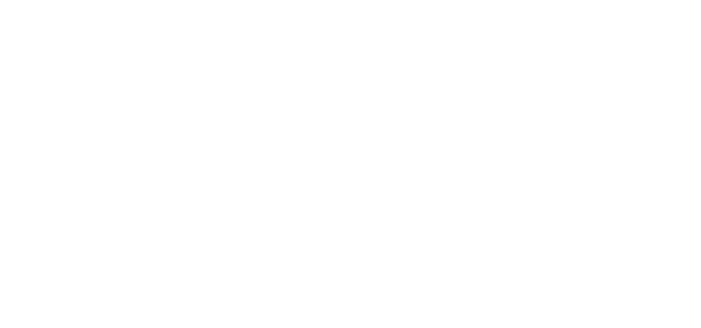

Now layer in the immediate context. Growth has slowed materially versus the pace implied by a 2034 target, and the IMF continues to flag binding constraints weak revenues and financial-sector vulnerabilities—even while expecting a modest rebound to around 4.7% in FY26–FY27.(IMF)

FIGURE 1: Bangladesh Macroeconomic Dashboard

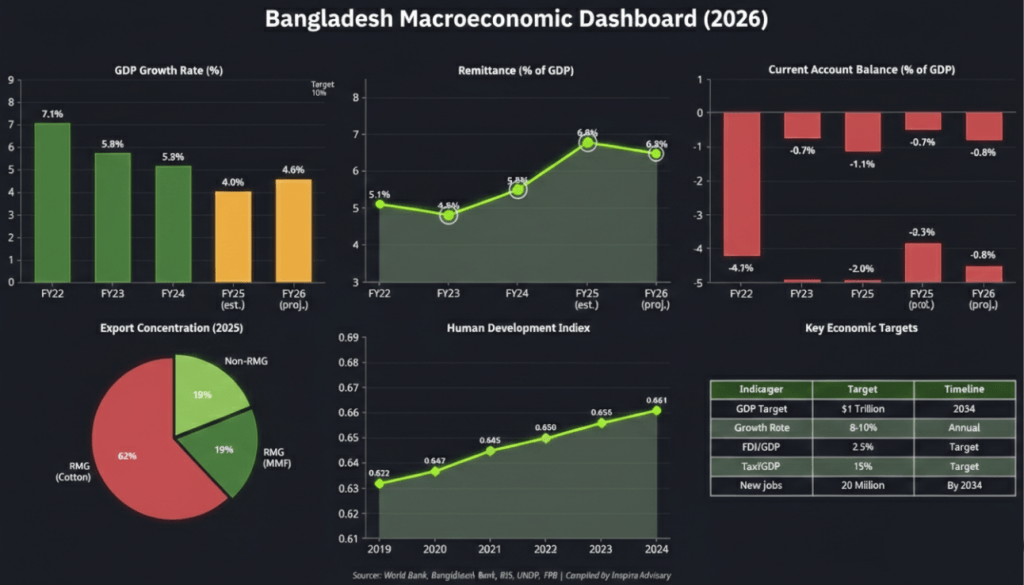

Our reading of the data (and of peer-economy trajectories) is that the “credible pathway” debate should start with a simple question: what are the bottlenecks that repeatedly cty to sustain high growth and what policy levers directly remove those caps? The five imperatives below follow that logic.

Where the $1T Path Tightens: Binding Constraints to Address First

If the incoming government wants the $1 trillion-by-2034 pathway to sound credible beyond slogans, it will need to show the intent early and repeatedly that it understands where the constraints sit in the growth engine. The point is not that Bangladesh lacks strengths; it is that the next phase of growth is more capital, capability, and coordination-intensive than the last phase. Countries that have pushed into sustained 7–9%+ growth, especially in Asia, typically combine three things at once: they attract long-term investment into tradable sectors, they move goods predictably across borders, and they build the institutional and fiscal “spine” needed to keep upgrading skills, logistics, and competitiveness over multiple political cycles.

One way to avoid cherry-picking is to look at a band of peers not one poster child. If we line Bangladesh up against a practical reference set in the region (for example Vietnam, Indonesia, the Philippines, India, and Sri Lanka), two signals show up quickly. First is investment intensity: Bangladesh’s FDI net inflows are reported at ~0.34% of GDP (2024), while several regional peers sit higher like are Vietnam at ~4.23%, Indonesia at ~1.73%, and the Philippines at ~1.93% (India and Sri Lanka are lower than the Southeast Asian cohort but still above Bangladesh at ~0.69% and ~0.77%, respectively). This does not mean “FDI solves everything.” It does mean that, for economies trying to climb into more sophisticated export baskets, FDI tends to be one of the fastest channels for technology diffusion, supplier upgrading, and global market access especially when domestic savings and long-tenor finance are constrained. (Trading Economics)

The second signal is trade and logistics performance, which is less visible in political debate but often acts like a hard ceiling. In the World Bank’s Logistics Performance Index (LPI) 2023 results, Bangladesh sits at a grouped rank of 88 (score 2.6), while peers that have diversified exports more quickly cluster higher India at 38 (3.4), Vietnam at 43 (3.3), the Philippines at 43 (3.3), Indonesia at 61 (3.0), and Sri Lanka at 73 (2.8). In practical terms, that gap shows up as longer and less predictable dwell times, higher compliance costs, and friction for new exporters, exactly the kinds of costs that discourage firms from moving beyond a narrow set of products and markets.

TABLE 1: Bangladesh vs regional peers—FDI intensity + LPI (2023)

| Economy | FDI net inflows (% of GDP), 2024 | LPI 2023 grouped rank | LPI 2023 score |

| 孟加拉国 | 0.34 | 88 | 2.6 |

| Vietnam | 4.23 | 43 | 3.3 |

| Indonesia | 1.73 | 61 | 3.0 |

| Philippines | 1.93 | 43 | 3.3 |

| India | 0.69 | 38 | 3.4 |

| 斯里兰卡 | 0.77 | 73 | 2.8 |

Data notes: FDI values are as reported for 2024. (Trading Economics) LPI ranks/scores are from the World Bank’s LPI 2023 results appendix.

A third constraint sits behind both investment and logistics: fiscal capacity.Even strong reform intent struggles to scale when the state cannot consistently fund the basics trade infrastructure, skills systems, industrial upgrading support, and targeted social protection that protects reform momentum. The IMF has noted Bangladesh’s tax-to-GDP ratio declined to 7.4% in its 2023 Article IV documentation), which underscores how thin the revenue base is relative to the size of the ambition. Put simply: a trillion-dollar target demands not only growth acceleration, but also state capability and fiscal room remove bottlenecks without repeatedly resorting to stopgap measures. (IMF)

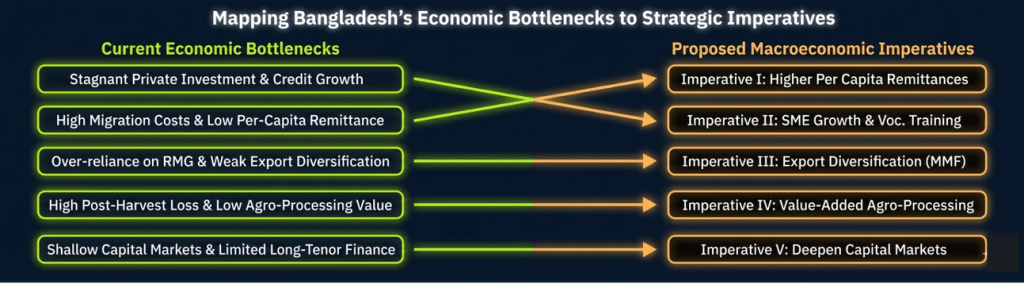

Finally, there is a macro-structural vulnerability that makes all of this more urgent: export concentration. one sector carries the bulk of export earnings, the economy becomes more sensitive to demand shocks, compliance shocks, and policy shocks in a small set of markets. Recent reporting continues to place garments at roughly ~80% of Bangladesh’s exports, is a remarkable achievement but also a clear signal that diversification is no longer optional if the goal is resilient high growth. (Reuters)

FIGURE 2: Economic bottleneck to strategic imperative mapping

Imperative 1: Raise remittance value per person, shift from “volume migration” to “value migration”

Bangladesh is often described as a remittance success story, and in absolute terms it is. But for a $1T pathway, the more revealing question is: are we maximizing earnings per person from the global labour market compared to peers?

TABLE 2: Remittance per capita comparison (2024)

| Country | Remittances received (current US$) | Population (2024) | Remittances per capita (US$) |

| 孟加拉国 | 27,032,642,224 | ~173.6M | ~156 |

| Nepal | 28,376,777,192 | ~29.65M | ~957 |

| 斯里兰卡 | 6,721,610,000 | ~21.916M | ~307 |

| Philippines | 40,279,405,932 | ~115.844M | ~348 |

| Viet Nam | 16,000,000,000 | ~100.988M | ~158 |

| India | 137,674,533,896 | ~1.4509B | ~95 |

| Indonesia | 15,701,686,400 | ~283.488M | ~55 |

The point is not to glorify any single comparator. It is to illustrate that countries can generate higher remittance inflows not only by sending more workers, but by improving occupation mix, certification, placement efficiency, and channel formalization so remittance per worker (and per capita) even if outbound numbers don’t.

A credible policy direction here is to treat labour migration as an economic competitiveness system, not a stand-alone social sector. That typically means:

- building a small number of “skills corridors”(e.g., caregivers, logistics and, technicians), where training, language readiness, ethical recruitment, and digital contracting are standardized end-to-end; and

- reducing leakage through better governance of recruitment costs, contract enforcement, and safer, more formal remittance channels.

This is one of the fastest ways to strengthen the balance of payments without creating an equivalent rise in import intensity.

Imperative 2: Upgrade SME clusters, shift from ‘survival firms’ to ‘scale-ready exporters’

If Bangladesh is serious about doubling its economy on schedule, the fastest route is not one “hero sector” doing all the lifting. It is thousands of firms especially SMEs becoming more productive at the same time: better processes, standards compliance, tooling, and supply-chain integration.

China’s early reforms enabled fast SME expansion, then policy increasingly used clusters, zones, and commercialization platforms move SMEs into higher capability activities. (World Economic Forum)

For Bangladesh, the underused opportunity is that we already have cluster-shaped industries (light engineering, plastics, repair ecosystems, parts and packaging) that can be upgraded systematically if skills, standards, and finance are bound into a single performance pipeline. Practically, that looks like:

- Cluster-linked TVET pathways respond to real production problems (quality, lead time, compliance);

- Shared services that SMEs can’t individually afford (testing, standards labs, tooling access, advisory); and

- Upgrade-linked finance (capital + capex) tied to measurable milestones (certifications, product complexity, export readiness, import substitution).

This is also where import substitution becomes macro-relevant: when SMEs can replace imported inputs/components reliably, they reduce FX pressure and make the export engine more resilient.

Imperative 3: Break export concentration, shift from ‘single-engine dependence’ to ‘diversified resilience’

A $1T Bangladesh cannot remain structurally dependent on one export engine. Concentration is not only a growth cap; it is a macro risk. Reporting continues to describe Bangladesh’s export base as heavily dominated by garments.Peer economies in Southeast Asia show diversification is a sequence: trade facilitation + investor confidence + reliable delivery systems a broader basket of products. Vietnam’s performance on logistics benchmarking is regularly cited as one indicator of that enabling environment. (OECD)

For Bangladesh, diversification can begin inside the garment complex (higher-value categories, man-made fibres, performance and technical segments) while scaling credible non-RMG lines aligned with SME strengths (components, packaging, select electronics assembly, medical supplies, pharmaceuticals, processed foods). But none of this works at scale if ports, customs, and standards capacity remain inconsistent.

FIGURE 3: Export concentration panel

Imperative 4: Unlock agro-processing value, shift from ‘raw commodity exports’ to ‘branded global products’

Bangladesh produces a large volume of agricultural goods, but producers do not capture global value processors, certifiers, and brand owners do. why agro-processing belongs in the trillion-dollar conversation: it is one of the clearest ways to create a second export engine that is more geographically distributed and less tied to a single sector’s global cycle.

The constraint is not creativity; it is the missing “export stack”: aggregation, cold storage, processing capacity, SPS/food safety compliance, traceability, and predictable logistics. When that stack exists, private investment follows because projects become bankable.

A practical near-term agenda is to pick a handful of products where Bangladesh already has comparative advansh, fruits, spices, select ready-to-eat categories), then coordinate the public goods that unlock scale: labs, certification pathways, cold chain nodes, and logistics reliability. Done well, this also supports employment outside major industrial corridors important for inclusive growth and domestic demand.

Imperative 5: Deepen capital markets, shift from ‘single-engine bank finance’ to ‘two-engine long-tenor investment finance’

The first four imperatives focus on building an export-and-productivity engine that can keep earning dollars and upgrading capability. But there is a quieter dependency underneath all of them: long-tenor capital. Cold chains and processing plants, SME upgrading, logistics infrastructure, and even skills corridors all need financing that matches their payback periods. When domestic savings and long-tenor finance are constrained, peer economies lean on capital markets as a second engine not a replacement for banks, but a complement that funds longer horizons.

In Bangladesh, that second engine is still idling. The capital market remains small relative to the economy, liquidity is thin, and corporate bond financing is close to negligible pushing companies back to bank balance sheets for everything from working capital to factory expansion.

TABLE 2: Comparative capital market depth snapshot (indicative 2024/25)

| Metric | 孟加拉国 | India | Pakistan | Vietnam | Indonesia |

| Market cap to GDP | ~10%–14%* | ~130% | ~8%–12% | ~55% | ~48% |

| Corporate bond market | <1% (negligible) | ~18% | ~1% | ~12% | ~2% |

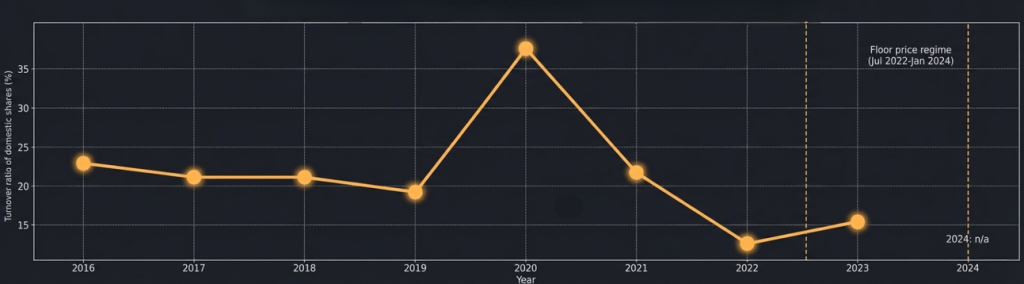

| Turnover velocity | Low (~14%) | High (~50%) | Moderate (~26%) | High (~40%+) | Moderate (~26%) |

| Derivatives | None (equity spot only) | World’s largest (vol.) | Active futures (DFC) | Covered warrants | ETF/futures |

Bangladesh’s market-cap-to-GDP varies by source and valuation date. For example, WDI/WFE data reports market capitalization at 19.54% of GDP in 2024, while liquidity remains low (turnover ratio ~14.5% in 2024).

The implications are practical. When the market is “spot-only” and thinly traded, sophisticated investors cannot hedge downside risk, so they stay away. When corporate bonds are missing, firms fund long-lived assets with bank loans deepening the asset–liability mismatch across the financial system. And when price discovery is periodically suspended, liquidity cannot compound over time.

So deepening the market is less about chasing a stock rally and more about expanding the instrument menu and investor base so long-term savings can flow into productive assets with predictable governance. The fastest route is to introduce a handful of instruments that structurally widen participation and provide risk management.

Start with thematic bonds (green, blue, and social) that package investable projects with clear use-of-proceeds and reporting. This is often what global ESG funds, sovereign wealth pools, and DFIs need to enter a frontier market with confidence bringing patient capital in tenors that conventional bank lending struggles to match.

Then scale sukuk issuance to mobilize domestic Islamic liquidity that frequently sits idle outside conventional interest-based instruments. Asset-backed sukuk can finance infrastructure and industrial utilities while offering a risk profile that many savers prefer over volatile equities.

Next, build REITs to convert illiquid real-estate wealth into traded instruments, so capital parked in land and buildings can circulate through a regulated market with transparency and diversification benefits.

Finally, introduce index-based derivatives (futures/options) with strong surveillance and risk controls. Hedging tools are a confidence mechanism: they give institutional and foreign investors a way to ensure portfolios and manage exits without forcing panic selling in the cash market.\

But instruments alone will not work if price discovery is intermittently suspended. Past interventions such as floor prices have frozen trading and weakened turnover; a deep market needs consistent rules, credible disclosure, and a functioning yield curve so that companies can price risk across maturities.

If Bangladesh wants a trillion-dollar economy that can survive shocks, it needs a financing system that funds the next decade of capex without turning every investment cycle into a banking-sector balance-sheet problem. Deepening capital markets is how the growth engine gets its second wing.

TABLE 3: Key 2034 targets

| Bottleneck | Key Indicator | Strategic Imperative | Recent Govt. Action |

| Inefficient Migration System | Migration cost $3,720 (vs. Nepal $1,088) | Higher Per-Capita Remittances | Labour Ordinance 2025 & ILO ratifications |

| Stagnant Private Investment | Credit growth at 6.23% (Oct ’25) | SME-led Industrialization | Banking Companies Act amendments |

| Concentrated Export Basket | 5-month export decline (late 2025) | MMF & High-Value Export Pivot | Reduced import duties on MMF inputs |

| Low Agricultural Value-Add | Post-harvest loss at 30% | Value-Added Agro-Processing | 10-year tax holiday for agro-processing |

| Weak Public Finance & R&D | Tax-to-GDP < 8%; R&D at 0.03% of GDP | Innovation & Fiscal Reform | NBR reform separating policy & admin |

Concluding remarks: credibility is earned through sequencing and measurable delivery

The $1T vision is not out of reach but it is unforgiving. It requires Bangladesh to raise its FX-earning capacity, push SME productivity into the mainstream, diversify exports beyond overconcentration, build a modern agro-processing stack, and deepen capital markets so long-term investment can be mobilized at scale.

What distinguishes credible transitions from aspirational ones is not the target year on a slide. It is whether the government can run two-to-three-year delivery sprints with clear metrics: faster logistics and customs, higher remittance value per worker, more bankable FDI projects, measurable SME upgrading in clusters, the first wave of export-grade agro-processing at scale, and visible progress on market depth (liquidity, bond issuance, and investor participation).

If those building blocks move together, the $1T headline stops being a rhetorical destination and becomes a pathway.

References

- The Illusion of Recovery: Bangladesh’s Economy on the Eve of 2026 — SANEM (January 2026)

- Crawling private sector poses first big test for next government — The Business Standard (January 2026)

- Broken trust: New govt faces battle to clean up banks — The Daily Star (February 2026)

- From uncertainty to confidence — Centre for Policy Dialogue (February 2026)

- World Bank cuts Bangladesh growth forecast for FY26 — The Daily Star (January 2026)

- After Bangladesh Votes: Stability Will Be Earned Through Delivery, Not Declarations — CSIS (February 2026)

- Will Bangladesh’s Interim or Future Government Reform Its Broken Labor Migration System? — Nepal Economic Forum / IOM (July 2025)

- Landmark Ratifications in Bangladesh — International Labour Organization (November 2025)

- MMF-based garment exports grow 14.1%, signal structural shift in Bangladesh RMG — Textile Today (February 2026)

- How agro-processing can secure Bangladesh’s export resilience — The Business Standard (April 2025)

- An Analysis of the National Budget for FY2025-26 — Centre for Policy Dialogue (June 2025)

- Low spending on R&D in Bangladesh alarming — Asian News Network (October 2023)