Key Takeaways:

- Massive financing gap: WASH sector in LMICs, including Bangladesh, faces billions in unmet investment needs despite high social and economic returns.

- Households overstretched: Over 80% of WASH spending in Bangladesh comes from families, often exceeding affordability thresholds and driving financial vulnerability.

- Blended finance underutilized: Less than 5% of global blended finance transactions reach WASH, hindered by small ticket sizes, weak pipelines, and low investor confidence.

- De-risking critical: Instruments such as guarantees, social bonds, and results-based financing can attract commercial capital into marginally bankable WASH projects.

- Ecosystem reform needed: Regulatory changes, enabling policies, and ecosystem support are vital to mainstream blended finance in WASH.

- Pipeline bottlenecks: Lack of investment-ready WASH projects limits capital absorption; project prep facilities, digital tools, and technical assistance can help scale.

The Global WASH Financing Challenge in Emerging Economies

The global push to achieve Sustainable Development Goal 6 (SDG 6) ensuring the availability and sustainable management of water and sanitation for all is facing a critical financing deficit, especially in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) such as Bangladesh. According to recent estimates1, the capital investments required to deliver universal, climate-resilient WASH services by 2030 total between USD 200–400 billion annually across LMICs. In contrast, actual financial flows into the sector remain a fraction of that. The hidden costs of poor WASH access—through increased disease burden, productivity losses, and degraded ecosystems—are estimated to exceed USD 500 billion annually.

Despite compelling evidence that every USD 1 invested in WASH yields USD 4–6 in social and economic returns2, the sector remains severely underfinanced. Globally less than 5% of blended finance transactions and under 1.5% of commercial capital mobilized are directed to the WASH sector3, making it one of the most underfinanced development priorities.

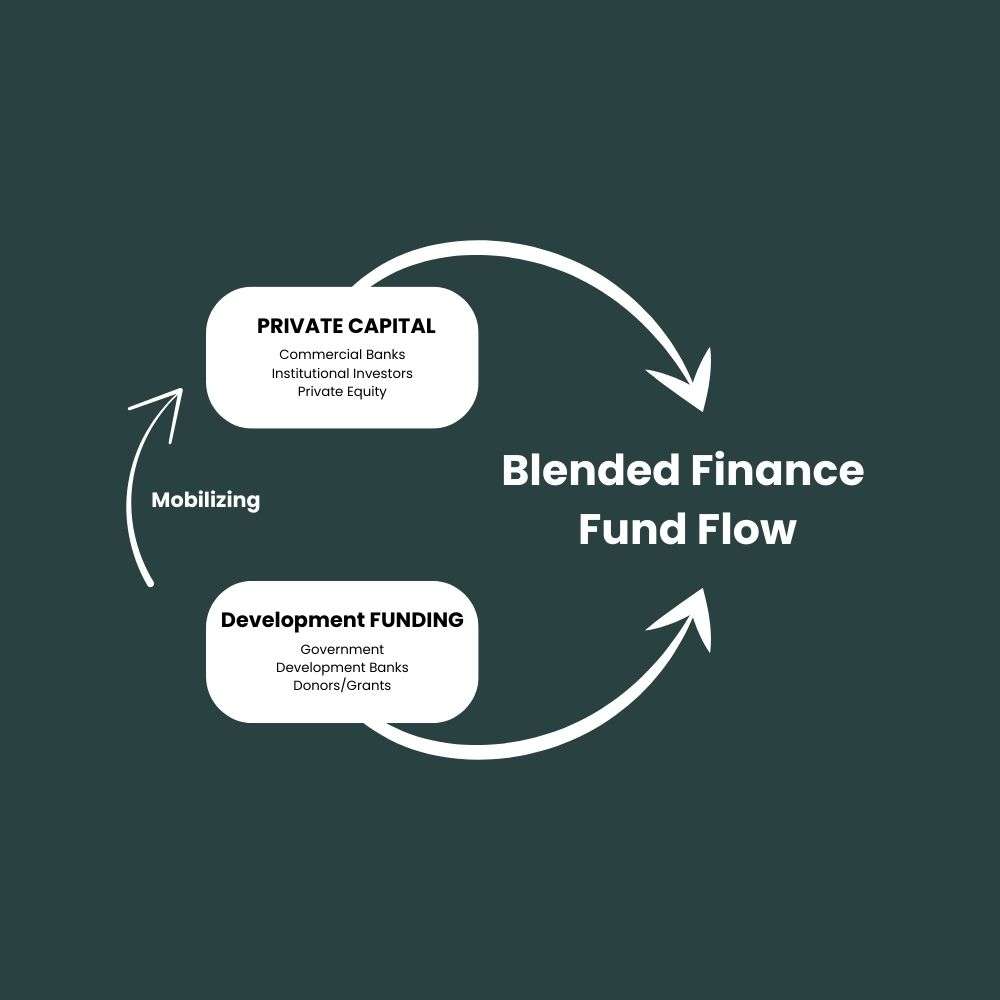

Blended finance refers to the strategic use of public or philanthropic capital to mobilize private investment in projects that deliver both social impact and financial returns. In the context of water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH), it addresses a fundamental challenge: while the sector generates strong social and economic benefits. This underrepresentation is due to a variety of barriers, including small ticket sizes, low perceived profitability, fragmented delivery systems, and inadequate project preparation mechanisms. This underrepresentation is due to a variety of barriers, including small ticket sizes, low perceived profitability, fragmented delivery systems, and inadequate project preparation mechanisms. Overcoming these constraints will be essential if blended finance is to contribute meaningfully to SDG 6.

Bangladesh’s Path to SDG 6: A Case for Catalyzing Private Capital

Despite commendable gains in water and sanitation coverage over the past two decades, Bangladesh remains significantly off-track in achieving SDG 6 by 2030. According to the WHO/UNICEF Joint Monitoring Programme (JMP) 2022 report, over 65 million people—more than one-third of the population still lack access to safely managed sanitation. Access to safely managed drinking water stands at just 48%, and disparities remain stark across geographies, income levels, and gender. These figures point to an urgent need for scaling solutions that go beyond traditional public service delivery models.

The challenge, however, is not merely technical it is fundamentally financial. The current structure of WASH financing in Bangladesh is heavily dependent on out-of-pocket household spending, which accounts for over 80% of total WASH expenditure. For low-income families, WASH costs can exceed 7.8% of annual income4, pushing many into financial vulnerability. Public sector contributions, while important, have plateaued and are unlikely to bridge the funding deficit alone especially amid fiscal tightening and growing climate adaptation demands.

Recent projections estimate that Bangladesh will require an additional USD 14.8 billion5 in public investment between 2023 and 2030 to achieve universal WASH access. Yet, this level of capital infusion cannot be met through public coffers and household spending alone. What’s needed now is a shift towards mobilizing commercial and blended finance to de-risk WASH investments, pool capital at scale, and enable a more resilient, inclusive, and climate-smart delivery of essential services.

Why Blended Finance can become a Game Changer for SDG 6 financing in Bangladesh

Global private capital estimated at USD 4.5 trillion in “dry powder (unallocated capital)6” is increasingly seeking sustainable and impactful investment opportunities. This vast reservoir of capital, held by private equity firms, development finance institutions, pension funds, and mission-driven investors, remains largely untapped for WASH primarily due to the perception of high risk, fragmented project pipelines, and limited visibility into financial returns. In countries like Bangladesh, where public budgets are constrained and households already shoulder over 80% of WASH financing, unlocking this capital is not just necessary, it is urgent.

Blended finance provides a powerful pathway to bridge this gap. By deploying concessional capital strategically through instruments such as first-loss guarantees, subordinated debt, social bonds, and results-based financing blended finance can reduce investment risk and make marginally bankable WASH projects viable. It also enables bundling and aggregation of smaller investments, improving scale and investor appeal. Crucially, it aligns financial returns with measurable social outcomes, a key requirement for attracting institutional capital into WASH.

Bangladesh is well-positioned to lead this shift. The country has a track record of financial innovation— from microfinance to mobile-enabled transfers and a growing ecosystem of public, private, and philanthropic actors aligned around inclusive development. What’s now needed is a coherent and collaborative approach to transform WASH from a subsidy-driven public good into a bankable investment domain. This means developing robust pipelines of investment-ready projects, aligning stakeholders across sectors, building tailored financing instruments, enabling supportive regulation, leveraging digital platforms for targeting and verification, and embedding transparent performance metrics.

Rather than viewing WASH as a fiscal burden, Bangladesh can reposition it as an investable frontier—one that delivers both measurable development impact and sustainable financial returns. Blended finance is not merely a funding technique; it is a catalytic strategy for scaling ambition into action, turning fragmented efforts into a coordinated market for capital, resilience, and equity.

Critical Approaches:

Despite promising signs and pilot initiatives, Bangladesh has yet to institutionalize blended finance as a central pillar of its WASH financing strategy. Unlike peer economies that are making notable progress— through national-level funds, climate finance integration, and social impact bonds—Bangladesh still faces fragmentation in project preparation, regulatory bottlenecks, and a lack of scalable financing models. To move forward, the country must reflect on understanding why blended finance remains underutilized in WASH. The main reasons lie in fragmented project pipelines, weak investment-readiness, and a lack of alignment between development objectives and commercial capital requirements. To overcome this, existing public and private financing models must be adapted. Development partners and government can provide concessional capital and guarantees, while commercial banks and impact investors can build dedicated WASH portfolios.

Equally critical is the role of financial regulators and ecosystem actors in creating an enabling environment. Introducing regulatory reforms to support instruments such as social bonds, guarantees, and results-based financing can significantly reduce risk perceptions. Central banks and financial authorities can also incorporate WASH into broader sustainable finance taxonomies, ensuring that water and sanitation are recognized as priority sectors for climate-resilient investment. In parallel, capacity-building for municipalities, utilities, and SMEs will be essential so that they can engage effectively with financial markets.

References

- Blueprint: Financing a Future of Safe Water, Sanitation and Hygiene for All” by WaterAid

- WHO (2012). Global costs and benefits of drinking-water supply and sanitation interventions to reach the MDG target and universal coverage.Geneva: World Health Organization.

- Convergence (2022). The State of Blended Finance 2022.

- Bangladesh National WASH Accounts (2020), jointly developed by Government of Bangladesh and UNICEF.

- SKS Foundation and UNICEF (2024). “Financing SDG 6: A WASH Investment Strategy for Bangladesh” – simulation estimates of required public investment under current exchange rate and pricing.

- World Economic Forum and BCG analyses: How blended finance could narrow Asia’s $2.5 trillion annual sustainable investment gap